Planet Four at the Planetary Science Subcommittee Meeting

The Planetary Science Subcommittee NASA Advisory Council met at NASA Headquarters earlier this month and was given a status update on all of the research areas in planetary science related to NASA missions. The meeting and the role of the subcommittee is to gather input and report information from the scientific community and public relevant to current and future NASA missions and programs.

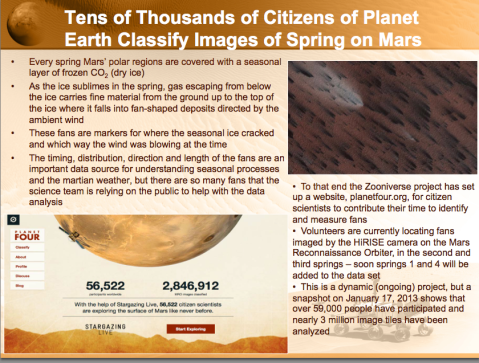

At the meeting Lisa May, Lead Program Executive for the Mars Exploration Program, presented on the status of the current and future Mars missions. In her presentation she talked about Planet Four and the work that you’ve all been doing marking the fans and blotches in the HiRES images or as she put it “tens of thousands citizens of planet Earth classify images of spring on Mars” Below is the slide from her talk.

You can read through the entire Mars Exploration Program presentation here.

Standing on the Surface

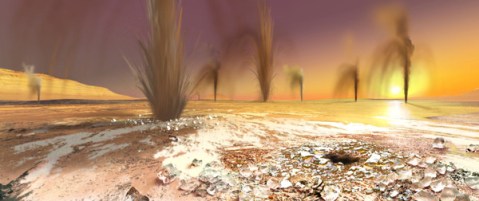

With the HiRISE images we show on Planet Four, you’re peering down at the Martian surface from above, seeing the fans and blotches that we want you to you mark. What would something like the image below look like from the ground if you were standing on the thawing carbon dioxide ice sheet during the Southern spring?

Well, if the geysers were actively lofting carbon dioxide gas and dust and dirt from below the ice cap up onto the surface and into the Martian air, you’d probably see something like the artist’s conception below.

Artist’s rendition of geysers on the South Pole of Mars – Image credit; Arizona State University/Ron Miller

How high are the plumes? Current estimates suggest that the geysers and material it lofts stay relatively close to the ground going probably no higher than about 50-100m into the air according to previous estimates based on fan length and simple deposition models. Though more likely, the geysers achieve smaller heights than that most of the time. To try and directly measure the geyser plume heights, stereo imaging where Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter pointed at the same spot twice at different look angles has been used. The two resulting HiRISE images are then combined to give height information in much the same way our brains combine the images obtained from our eyes, each viewing at a slightly different angle and position than the other, to get depth perception. HiRISE would have been able to see the geyser plumes above the ground in the combined stereo pairs, if the majority achieved heights of 50-100 m, but no image to date yet has caught a detection of a plume. So that suggests that the geysers may not reach these maximum heights but instead only go up to maybe 5-10m off the ground.

Your clicks may be able to help constrain better the height of the geyser plumes. With your classifications, we will have the largest sample of fan lengths and directions and blotch radii ever measured on the Martian South Pole. With the fan lengths from your markings, a measure of the terrain’s slope, and an assumption for the particle size of the Martian dirt/dust being entrained by the escaping carbon dioxide gas, you can estimate the maximum height needed to loft the material for it to fall at a given distance from the geyser for a range of wind speeds.

Martian Timekeeping

A year on Earth is 365.25 days, but it takes Mars nearly twice as long to complete one revolution around the Sun. With 668.6 sols (a sol is a Martian day), how do scientists keep track of the Martian time and date?

A Martian sol happens to be 39 minutes and 35 seconds longer than Earth’s. Dating back to the days of the Viking landers, sols are kept on a 24 hour clock. With the extra 40 minutes, Martian hours, minutes and seconds are slightly longer than their Earthly counterparts. That can make it a bit difficult to have a Mars time wrist watch.

The Martian calendar is not broken up into months like we have on Earth. Instead planetary scientists use the position of Mars in its orbit to tell time and mark seasons. They use the solar longitude L_s (pronounced “L sub S”) which is the Mars-Sun angle to keep track of the year. L_s=0 degrees is when Mars is at the northern vernal (Spring) equinox. L_s=90 degrees when at the Northern Summer Solstice) 180 degrees at the Northern Autumnal Equinox and 270 degrees at the Northern Winter Solstice. Just think the opposite to get the specific season for Mars’s Southern Hemisphere.

This upcoming February 23rd will mark the Winter solstice in the Northern hemisphere (Summer solstice in the Southern hemisphere). So on the South Pole there should be some seasonal fans, like the ones you’re mapping on the main classification interface, currently visible to HiRES where there is still thawing carbon dioxide ice.

You can find out more about the Martian Calendar and the dates of future solstices with this post by the Planetary Society.

Interesting Features to Mark

The project has only been running for one day, and you’re already finding interesting things in the images you’re classifying. We’d like you to help us study them more by marking them in the classification interface and in the Planet Four Talk discussion tool.

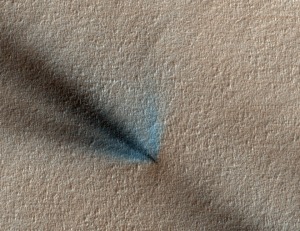

The majority of the fans and blotches that you mark will be completely dark. You may come across a fan that has bright blue or white streaks in it. Like these:

We believe that the bright stuff is carbon dioxide frost that has condensed from the gas coming out of the geyser and back onto the surface of the ice sheet. Observations have shown that the bright streaks are variable over time. Knowing where they are in the images will help us monitor them.

If you see a fan like those above, mark it with the fan tool as your normally would and but also mark it with the Interesting Feature tool. Please also highlight your discovery on our discussion tool (Planet Four Talk) by clicking on the Discuss button after submitting your classification and label the image with #frost.

The Interesting Feature drawing tool can be found below the Blotch drawing tool in the classification interface. (see the red arrows below in the screen shot).

You may have also spotted bright roundish small blobs in the images where there are dark fans or dark blotches. Like these:

These are bright roundish features are boulders and we think in on region on the South Pole they may have some role in the formation of fans. If see an image like above or below:

Please also mark these with an Interesting Feature Tool after marking blotches and fans in the images and highlight the boulders on Planet Four Talk with #boulder

More on Planet Four

Greetings Earthings,

Hi, I’m Meg Schwamb a postdoctoral fellow at Yale University and member of the Planet Four Team. The response from BBC Stargazing viewers has been amazing and we want to thank all of you for participating in the project. Thanks for helping us explore the surface of Mars and study the seasonal processes ongoing on the fourth planet from the Sun.

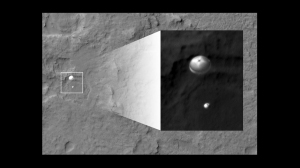

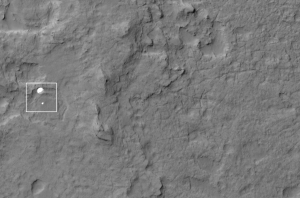

The images we’re asking you to classify come from HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging NASA’s camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). MRO has been orbiting Mars since late 2006. HiRISE is a high resolution camera that is capable of seeing features the size of a dining room table on the surface of the Red Planet. This camera has been giving us the most detailed images of Mars that we can use to study how the surface changes with differing seasons and explore the geology of Mars from orbit. In addition MRO has helped keep rovers like NASA’s Curiosity ad Opportunity safe, with the capability to identify large rocks at potential landing sites that could damage a rover during landing.You might already be familiar with HiRISE images. MRO and HiRISE caught Curiosity on August 5, 2012 in the act as it was parachuting down to the surface to it’s future home at Gale Crater.

NASA’s Curiosity parachuting to the surface of Mars imaged by HiISE and MRO Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona

On Planet Four, you’re seeing images of the South Pole of Mars. We are asking you to mark these beautiful dark fans and dark blotches that appear and disappear during the Spring and Summer on the South Pole of Mars. During the winter carbon dioxide (CO2) condenses from the atmosphere onto the ground and forms the seasonal ice sheet. The ice begins to sublimate in the spring, and the seasonal cap retreats. There we see over the Martian spring and summer these dark fans and blotches. They begin to appear in the Southern spring when the ice cap begins to thaw and sublimate back into the atmosphere. The fans and blotches then disappear at the end of the summer when there is no more ice left.

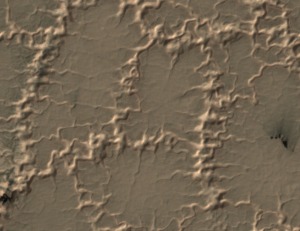

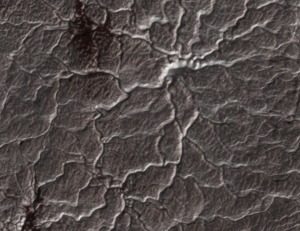

Later in the spring/summer season as the ice thins that we see these channels have been carved in the surface. Many originate from a single point and radiate outward. Others just like a patches of swiggly lines crisscrossing or in orderly rows. Those ridges are channels in the soil that are sculpted by carbon dioxide gas. These veins in the images are what we call “spiders” or araneiform terrain.

spiders-like or araneiform terrain with channels carved by carbon dioxide gas. Here you can see there are some fans that appear to be originating from geysers that develop in these channels

Here’s how we think they form: In the spring/ summer when the sun come up the sun heats the base of the ice sheet the ice sublimates on the bottom creating carbon dioxide gas that carves these channels or spider-like features. The trapped carbon dioxide gas is rushing around the bottom carving these channels and tries to exploit any weaknesses in the ice sheet. If it can the gas propagates through cracks in the ice sheet the gas escaping into the atmosphere in geysers. The gas bringing along dust and dirt to the surface that we think get blown by surface winds into the beautiful fans we ask to mark or if no wind the blotches we ask you to map. This morphological phenomenon is unlike anything seen on Earth. You can learn more about all of this process we think is happening on the surface in our previous blog post.

We want to study how these fans form, how they repeat from Spring to Spring and also what they tell us about the surface winds on the South Polar cap. We only have very few limited wind measurements from spacecraft we’ve landed on Mars. If the fans are places where the wind is blowing, then they tell us the direction and the strength of the wind. Blotches then tell us where there is no wind.Your mapping of the fans and blotches would help provide largest surface wind map of Mars.

Over 10,000 participants worldwide have helped classify 340,052 MRO images. But we still need your help. There are many more images still waiting to be mapped. Help us out at http://www.planetfour.org/ today.